And happy Thanksgiving to you too!

When I was a kid, my dad would sometimes come for Thanksgiving. My mom made chicken because she said turkey was too dry and we’d choke on it. But sometimes the chicken didn’t get cooked all the way through; my mother called this ‘al dente.’ It’s a wonder she didn’t kill us. The McCormick chicken gravy was always loaded with lumps I would squish against my plate; it was one of those gross things you can’t resist doing. Then there was the frozen brick of Bird’s Eye creamed onions that would become a congealed mess with a little hit of ice at the center, Bird’s Eye cut green beans with freezer burn because they were bought back in February when they were on sale, a wobbly cranberry sauce wearing the impression from the inside of the can— this was strictly for the grown-ups, stuffing— sometimes it was ‘homemade’ with Wonder Bread, sometimes it was Stove Top. We only got Bird’s Eye or Stove Top on Thanksgiving, the rest of the year it was Econo Buy and Montco. The only thing homemade here was the mashed yellow turnips (rutabagas nowadays)—despite the acrid dried parsley. This is the only part of of this space-age convenience meal I still make. With fresh parsley. Italian flat-leaf parsley. Organic Italian flat-leaf parsley. Purchased after the grower tells me a charming story about how his great, great grandmother came over from Italy with one parsley seed in her pocket and how he honors the earth buy planting only when the earth is in energy alignment with the spirits of the rootsayers.

All this ‘pilgrim’s bounty’ landed on a vinyl tablecloth with a turkey print all over it: the chicken on the good china platter inherited from my grandmother, the ‘blue plate’ dishes from the Americana promotion at the A&P, various flatware from promotions at the Grand Union, goldenrod colored plastic glasses made To look like logs from god only knows where. Then it would all go to hell. My mother would start with my dad. I would just keep eating and hope it would blow over. Sometimes, I would try to add small talk about stuff like the price food going up or gas or some pertinent economic issue, but that didn’t help, the argument was like a rolling stone that bounced over any obstacle in its path. Finally, my dad would put his napkin on the table and get up and leave. “Well, it’s just you and me now,” my mother would say defiantly. Sometimes there was a ham instead of chicken. This was suctioned out of a candy corn shaped can for the gourmet treatment: a lattice pattern of knife slashes across the top dotted by cloves so it looked quilted, finished with pineapple ring, and soaked in a brown sugar sauce. This would pair with canned candied yams and, in a nod to our German heritage, Bird’s Eye German-style green bean and spaetzle; for dessert, a Hostess apple pie a la mode (my mother took French in high school, of which she remembered exactly two phrases: a la mode and merci beaucoup).

When my father couldn’t visit, Thanksgiving took a strange turn. Sometimes we would join my Nana, who was not my grandmother but a lady who used to babysit me. We would celebrate with her fortysomething daughter (who still lived with her), her fiftysomething son (because his grown kids by his ex-wife weren’t speaking to him), and his girlfriend. The first time we went, I remember I was impressed with the table setting: gleaming silverware, china plates with gold trim, crystal glasses, a lace tablecloth, real candles, and a real flower centerpiece. Nana showed me a dish she was making: sweet potatoes with mini marshmallows on top. Wow. Marshmallows for dinner! I told her I wanted a lot of that. It is still one of the top ten worst things I ever put in my mouth. Then BAM! Dinner is served! Her son is clearly loaded and now he’s waving an electric knife back and forth over the turkey and god only knows what he’s talking about. His girlfriend’s wig is askew and she apparently subsists on little bottles of Jim Beam. Is she trying to limit her intake? Nana’s daughter has been slacking off on the lithium again and tells everyone “you need to be careful because they can hear you.” Who’s they? But the real entertainment is when, out of nowhere, a black cat jumped onto the table. I watch as cat hair, highlighted by the light from the chandelier, slowly settles on everything. I’m full. Amazingly, this scene would repeat itself almost exactly every time we had Thanksgiving there. Strange.

Sometimes Nana was abducted by her family in New York, so my mother took another stab at Thanksgiving. It would be a trendy Friendsgiving now. She would invite Nana’s daughter and some people she met around town who didn’t have anywhere to go. Normally, this would seem like a very nice thing to do, except these particular people didn’t have anywhere to go because they were living in hotels and they were living in hotels because that’s where the state put them when the state closed down all the mental institutions. Thomas, my mother said, was a real American Indian, a fact that he advertised by wearing lots of turquoise jewelry over his polyester three piece suit. Every chance he got, I got a BIG hug from Thomas. My mom said Thomas told her this was the best Thanksgiving ever. No shit. Then there was Judy, she used to be a nurse at Massachusetts General. She was already lit when she arrived and staggered up the stairs, so my mother paired her with Billy who was so drunk he had wet his pants and didn’t even notice. Maybe he spilled something. It was hard to tell. Then Isabelle and her little dog. She wasn’t a former mental patient but she was deaf and very, very, extremely, loud; at least she was sort of normal. She had a it tough and worked her whole life in some lace factory. Then there was Betty Boop (not her real name). She had been a Rockette and on national TV with the June Taylor Dancers on the Jackie Gleason Show. My mother loved Jackie Gleason and would talk endlessly about him like she knew him, which was kind of strange. Anyhow, Betty went nuts after the birth of her second kid and spent many years in and out of mental institutions and getting shock therapy. Now she spent all day wheeling her dog around town in a baby carriage while drinking coffee, smoking, and wearing way too much make-up. And then there was Harold. Ugh. He wanted to get it on with my mom and kept grabbing her and trying to kiss her. My mom was always like, “Oh, he’s harmless.” I would have just the worst spinning feeling from all this. Please Dear Lord let it be over.

With the cast assembled, my mom loved to play dictator, everyone had their little job. We put a little pressed wood table together with a rickety card table and threw a stained tablecloth over the whole thing. The tables weren’t the same height, a fact that no one seemed to notice since everyone tried to place something across the ledge only to have it tip over and exclaim, “Oh my goodness! What happened?”. My mother set this all to music. She had only two records: one was Mario Lanza’s The Student Prince and Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker by Boston Pops. Once the food hit the table, it looked like a bunch of raccoons had gotten into the trash. Isabelle sat her dog on her lap feeding him the whole time until he finally puked. My mother was like, “Oh don’t worry, let me get you a napkin.” Dog puke stinks. Everyone made sure to compliment my mother profusely; this was the best meal they ever had. And I was the ungrateful little snot sitting in the middle of this. Future organic flat-leaf parsley using snot.

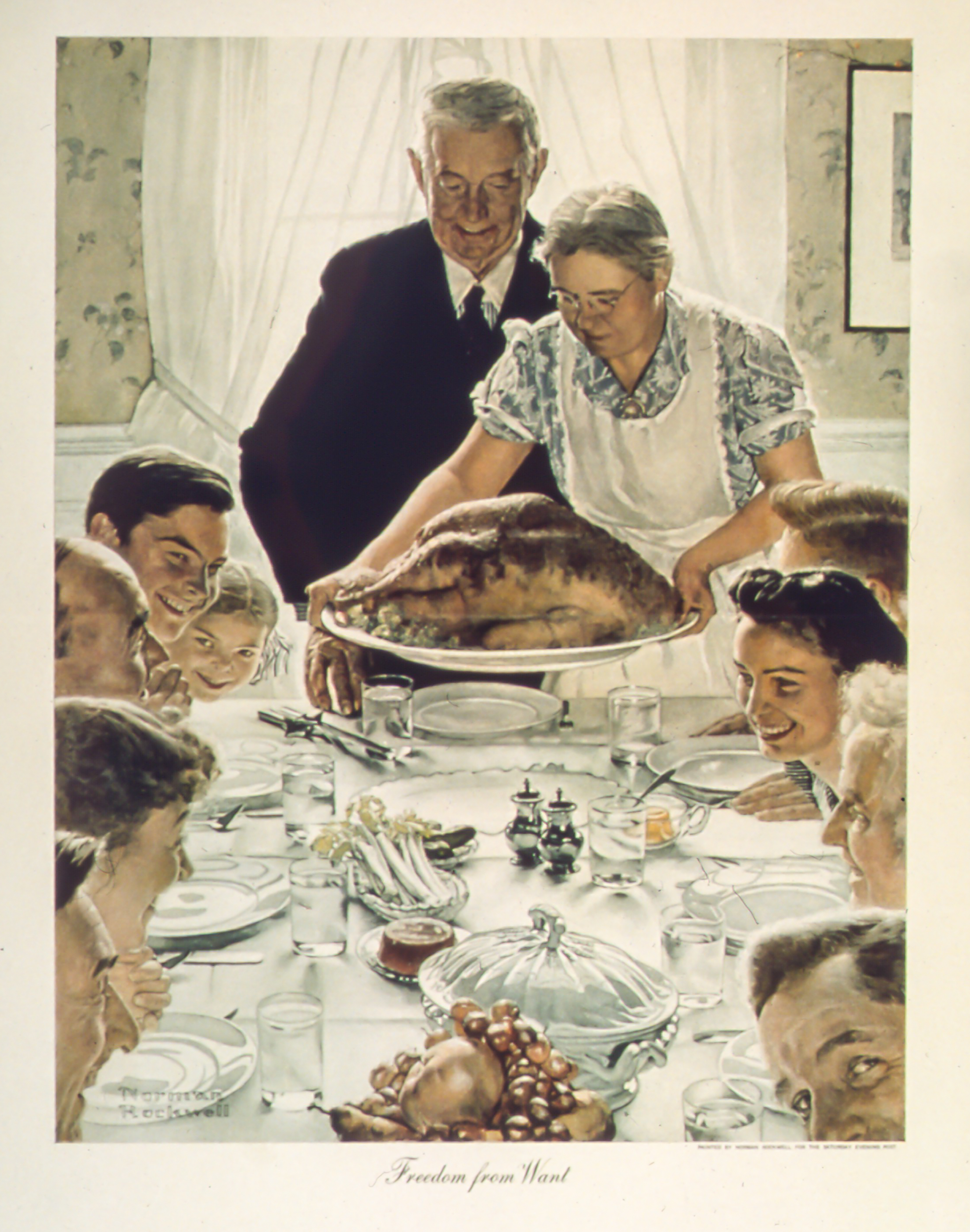

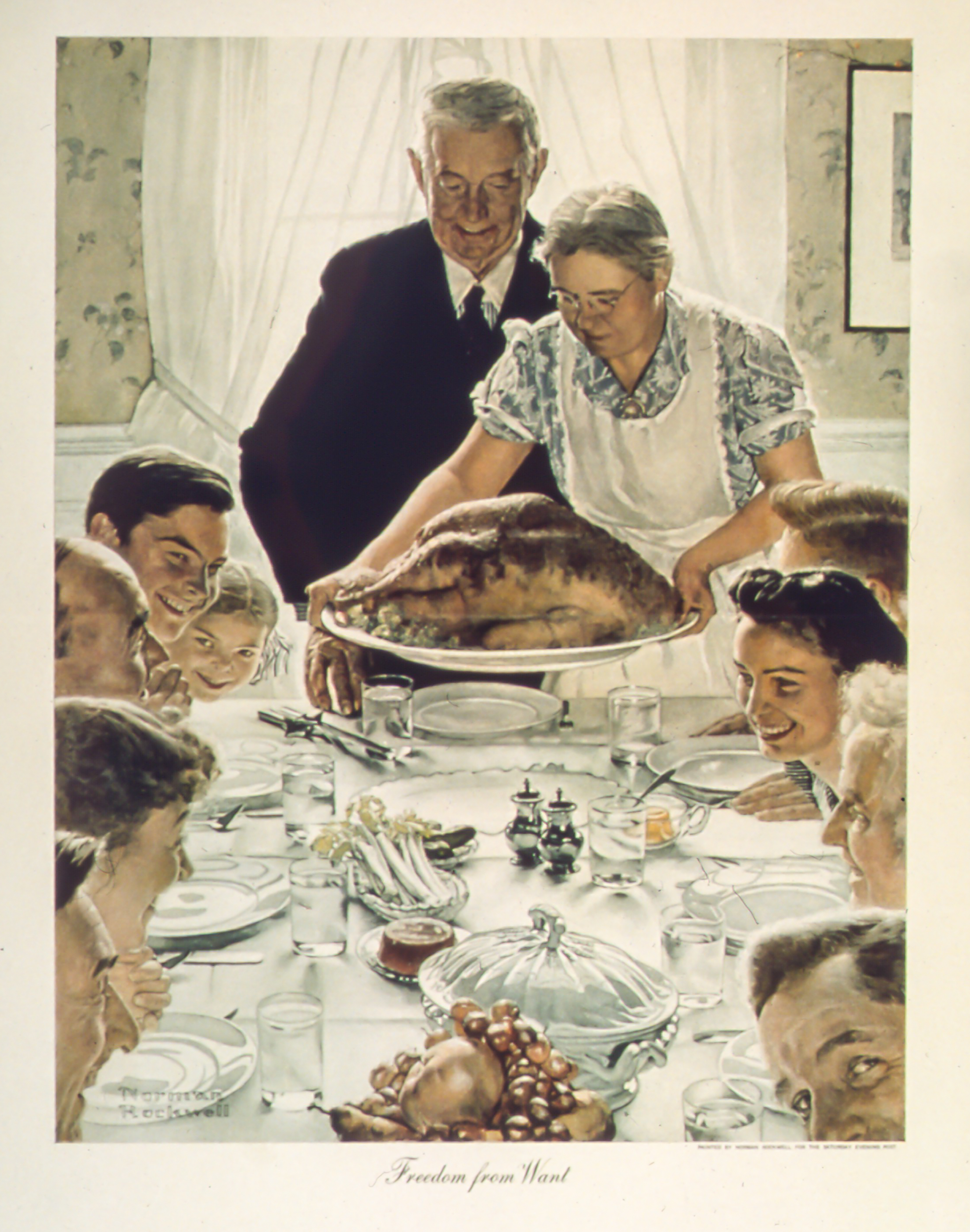

Once, I was looking at Norman Rockwell’s famous Freedom from Want painting on my mom’s calendar— my mom loooooved Norman Rockwell and would buy anything with his stuff on it— and I told my mom’s friend Mary Anne I wished my Thanksgivings were like that and Mary Anne, who was one of twelve in a big Irish Catholic family, looked at me like I had three heads and twelve eyes and said, and I quote: “Are ya kiddin’ me! Rockwell is a goddamn twisted sadist. Nobody’s goddamn Thanksgiving is like dat, he’s like fucking Walt Disney and everything’s all fine an dandy. Let me tell ya: nostalgia is for shit and you can take that to the bank.”

But she didn’t stop there, she pointed to the picture: “Lemme see here. Ok, ya see Gramma back there? She look like some nice old lady, right? She’s serving da turkey like it the goddamn baby Jesus an the damn thing is drier than kindlin’. Granpa? He’s stickin’ close to her so he can maybe get a leg. All he thinks about ‘gotta get a leg, gotta get a leg’ over and over like a dog. ‘Cause that’s what she trained him to be, her goddamn dog. My folks ain’t here ‘cause they on the back porch fightin’, cousin Billy ain’t in the picture cause he’s passed out on the couch, cause there was three pubs between his apartment and Gramma’s house, my sister Margaret, she ain’t here cause she away at a ‘school’ for pregger girls and Gramma says God is gonna to punish her good. My brother Billy ain’t there ‘cause he a fag and Gramma says he goin’ to hell. Patty ain’t here cause she got divorced and Gramma says she goin’ to hell too. Cousin Danny, the guy in the bottom right, he divorced too, but he gives Gramma special candy so apparently he ain’t gonna go to hell. Ya see that old lady behind Danny, that’s Gramma’s sister Betty. She ain’t never been married. She doesn’t give a shit a bout nothin’ so long as she gets dessert. Behind her, ders my sister Catherine, she fuckin’ perfect, she go to mass every day, everybody go on and on and on ‘why can’t youse be like Catherine.’ All dat church don’t do her no good ‘cause she’s the meanest bitch I ever seen. And Gramma is gonna leave her all her jewelry; well who cares! Ain’t nobody want all her ugly shit anyways. That young guy up by Gramma— I‘m jus smushing all together like 20 years or somethin’— anyways he’s my brother, he’s up front cause he told Gramma he was thinking about goin’ in the priesthood; Gramma looked like she had a hit a dope, ya know what I mean? So now he’s her favorite. If he gonna be a priest I’m fuckin’ Einstein, ya know what I mean? No way he’s gonna be a priest, he fucks everything he sees. Gina tells me he’s been giving everyone the clap an he got fired at A&P for sticky fingers. Dat guy behind him, dat could be Uncle Jerry; I don’t know too much about him; he might been a nice guy; his wife died now he practically lives at the pub. He practically lived dare before, but now it’s full-time. Oh, and dat couple on the bottom right, I’m gonna make them my Aunt Jean and her husband, I forgets what his name was, anyways they take the cake! They talked Gramma into getting a loan on her house for ten grand. Very, very, very big money, you hear me? Hey were gettin’ in on the ground floor of some deal that was gonna make Gramma rich, everybody rich. I dunno what happened, but six months later they was vamoose. Gone. Many years later, I heard they was maybe in Florida, but we ain’t never seen them again. An get dis, the goddamn hairy Labriola family down the block? Everybody say, ‘Oh why can’t we be like those people, they love, love, love, each other. Nobody ain’t never passed out on thems front steps. Family, family, family, all about family. Everybody love. Even when they fight. When they fight, it sound like a goddamn opera, when we fight, it sound like animals.’ Well, you guess what? Two days before Christmas what happens? Angelo Jr. stabs to death he’s father Angelo Sr.! Well he had a heart attack at the hospital, but it was cause he got stabbed. Nobody ain’t never got stabbed at my house! Thanksgivin’ ain’t like that picture for nobody, dat’s made up shit to make us people feel like crap. Oh, and den, after Joe and me got married and we’s went to his house….don’t get me started. So dare’s your happy fucking Thanksgivin’. Jus be glad youse ain’t dead. Everythin’ else is gravy, GRAVY! Ya hear me!”

“Oh, and Merry Fuckin’ Christmas, don’t even get me goin’ on that one!”

“You makin’ me hungry talkin’ about Thanksgivin’. Lemme see what you has in the fridge here.”

Copyright © 2015 MRStrauss • All rights reserved